From Aggie Horticulture, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, Texas A&M University System

by Julian W.

Sauls, Ph.D. Professor and Extension Horticulturist

T - Bud Graft

In this

presentation on T-budding, 29 images are included to illustrate

the finer points of the technique.

While it is called T-budding, the process being described is

technically an inverted-T. This same procedure is also used to bud a

number of woody plants, including all citrus types, peaches,

nectarines, plums, apples, grapes, roses and others. T-budding can be

done anytime the bark of the rootstock is "slipping", i.e., the bark

separates easily from the underlying wood. For citrus in subtropical

areas, the bark slips from early spring through late fall. In

greenhouse production and in tropical areas, the bark slips anytime the

plant is in active growth, which is practically year-round.

Materials

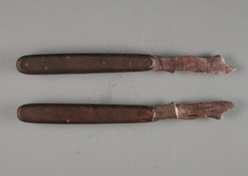

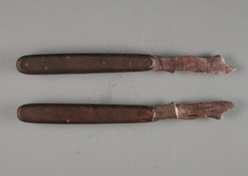

Budding knives are extremely thin-bladed, with both right-handed and

left-handed versions. Image 1 shows opposite sides of a typical

right-handed budding knife- the side of the blade shown on the upper

knife is flat (unground) while the opposite side (the lower knife) is

ground down to the cutting edge. Many budders prefer high carbon steel

blades (rather than stainless steel) because they are more easily kept

sharpened to a razor edge.

Fig.

1

Right handed budding knife

The best of pocket knives are usually too thick-bladed to use for

budding. Utility knives with replaceable razor blades may be the better

choice. Blade thinness and sharpness are critical for successful

budding, as a thick or dull blade causes jagged cuts which do not

"take" readily.

Most budding tape is either clear, very thin polyethylene (at left in

Image 2) or somewhat thicker, opaque polypropylene. For home use,

strips can be cut from plastic sandwich bags. Neither electrical nor

"Scotch"-type tapes are recommended, though plumber's teflon tape

should work. The purpose of the tape is to exert a little pressure on

the inserted bud, to keep out excess moisture and to protect the bud

while the cut surfaces heal and begin to grow together.

Fig.

2

Budding tape

Seedling rootstocks of at least pencil diameter are usually the easiest

for beginners, although both smaller and much larger stocks can be

budded successfully. Image 3 shows three seedlings, all of which are

buddable. The seedling on the left was used for most of the subsequent

images of the actual budding process.

Fig.

3

Seedling rootstocks

Budwood for home use may be collected from any tree of the desired

variety- in most cases from friends, relatives, neighbors or local

nurseries. Each of the major citrus-producing states have budwood

certification programs which sell virus-free budwood to residents.

Because citrus trees typically have four or more growth flushes

annually, there should always be usable budwood.

In Image 4, the budstick at left is the best, the middle one can be

used with good technique, but the one at right is too angular. Each of

these three budsticks represent a different growth flush of the same

branch--the one on the left having developed in the early spring, the

middle one in late spring and the one at right in mid-summer. If you

look closely at the second bud up from the bottom on each budstick, you

will see that the bud and surrounding twig on the left most budstick is

round and plump while that of the right most is angular and skinny. If

left on the tree, the budstick at right would have looked like the one

in the middle after the next growth flush and then like the one on the

left after the second growth flush.

Fig.

4

Comparing budsticks

Budwood should be placed in closeable plastic bags and kept cool until

use. For storage longer than a couple of hours, the bag should be

placed in the refrigerator. Under such conditions, citrus budwood can

be stored for several weeks, if absolutely necessary.

Preparing the

Stock

Unless local conditions warrant budding very high on the rootstock,

about six inches above ground should be adequate. In the area to be

budded, carefully clip off all leaves, thorns and side twigs. For

optimal success, the area where the bud is to be inserted should be

fairly straight with about an inch or so between two remaining leaf

bases. This distinction will become clear as you look at the next five

images.

Image 5 is a side view showing the relatively shallow depth of the

point of the budding knife as it starts to make the vertical part of

the T-incision. The bark is quite thin and very soft, so a sharp knife

easily penetrates and cuts the bark with very little pressure. There is

no reason to cut into the wood- with practice, you can "feel" the knife

tip as it penetrates the bark and makes contact with the wood.

Fig.

5

Side view of the cut

Images 6, 7 and 8 show the progression of the horizontal cut at the

bottom of the vertical one. Note that the cutting edge of the blade is

angled upward sharply, probably at about 45 degrees. To start the cut,

place the blade edge at the left side of the vertical cut as shown in

Image 6, press it firmly but lightly into the bark (again, with

practice, you can "feel" when the blade penetrates the bark).

Maintaining the same light pressure and angle of the blade, "walk" the

blade across the stock (do not use a sawing motion!)

|

|

Fig. 6

Beginning the horizontal cut |

Fig. 7

Middle of the horizontal

cut |

Note the position of the thumb and forefinger in each image, since

their position shifts to the right as the cut is completed. In Image 6,

the wrist is cocked or bent backward, it is nearly straight in Image 7

and it is slightly curled inward in Image 8--solely by moving the wrist

and forearm slightly to the right from beginning to end of the cut.

Also, note how the knife edge lifts up the bark during this cut-that is

why the blade edge is angled sharply upward. As you examine the

completed incision in Image 9, notice that the bark flaps at the bottom

of the inverted T are still raised from the stock. These raised flaps

provide a guide for easier insertion of the bud.

|

|

Fig. 8

Finish of the horizontal cut |

Fig. 9

Completed inverted-T incision |

Cutting the

bud

The most critical aspect of budding is cutting the bud itself-it is

only a very thin slice of bark and a sliver of wood beneath the bud,

but it must be cut evenly and smoothly. The flat side of the blade must

be flat against the budstick (Image10), with the knife held at about a

45 degree angle to the budstick (Image 11). With the thumb braced along

the stick below the bud, simply draw the knife towards the thumb

(again, no sawing or rocking motion!), keeping the blade flat against

the stick to prevent it from cutting too deeply (Image 12). If the

blade remains flat against the stick, it will normally slice under the

bud and exit below it (Image 13).

|

|

Fig. 10

Side view of start of bud cutting |

Fig. 11

Start of bud cutting |

|

|

Fig. 12 Middle of bud cutting |

Fig. 13 Finish of bud cutting |

Sometimes, the budwood won't cooperate or the knife cuts too deeply

into the wood to exit. If the cut is a smooth one, simply back the

knife out and cut off the bud piece about half an inch below the bud,

with the blade edge angled downward as shown in Image 14. Examine the

excised bud piece in Image 15. It is less than an inch long, with the

bud itself near the middle. Obviously, it is just a very thin slice of

the budstick. More importantly, the cut surface as seen in this side

view is smooth and very straight; this bud will "take"!

|

|

Fig. 14

Bud cut

off, if necessary |

Fig. 15

Completed bud ready to insert |

Inserting the

bud

Place the upper end of the bud piece beneath the bark flaps at the

bottom of the inverted T and gently but firmly push it upward with your

thumb (Image 16). With a good stock and slipping bark, the bud will

easily slide under the bark, lifting it from the wood as the bud is

pushed upward. Slide it upward until the entire bud piece is beneath

the bark of the stock (Image 17). Note that the sides of the bud piece

are completely beneath the bark on both sides of the vertical part of

the T, with the actual bud about centered between the two cut edges of

bark. A side view of the inserted bud (Image 18) shows

|

|

Fig. 16

Start

of bud insertion. |

Fig. 17

Complete bud insertion. |

mostly the bark of the stock, with the bud, its attendant thorn, the

leaf base and a little of the bark of the bud piece.

Start wrapping the bud below the incision, making several turns around

the stock until the entire bud and incision are covered, finishing with

the end of the tape tucked beneath the last turn (Image 19). During

wrapping, maintain firm pressure on the tape, but don't stretch it so

hard that it breaks. If the tape breaks, remove it and start over with

a new strip, using a little less pull.

Beginners will often put two or even three buds on a stock in hopes of

increasing the odds of success. Since good technique has better than 98

percent success, multiple buds will not overcome poor technique. It

would be more useful to practice slicing buds from a budstick until you

can consistently cut them like the one in Image 15. Even then, save the

unused budsticks until after unwrapping-just in case you need to rebud.

|

|

Fig. 18

Side view of the inserted bud |

Fig. 19

Bud

wrapped with polyethylene tape |

Forcing and

Aftercare

After 12 to 14 days, healing and union should have occurred, so remove

the tape. The easiest removal is to simply make a vertical cut through

it on the backside of the stock away from the bud, then slip it off.

You can also cut it at the tuck and unwind it.

If your technique was somewhat lacking or if this is just one of those

one or two percent that simply don't take, the bud will be mostly brown

or blackish (Image 20), and may just look rotted. In this case, select

another spot on the stock and rebud it. A live bud will still be as

green (Image 21) as it was when you inserted it two weeks earlier. The

small stub of the cutoff leaf petiole will have turned yellow and it

will readily fall off, if it didn't come off during unwrapping.

|

|

Fig. 20

Bud failure |

Fig. 21

Live bud

ready to be forced |

Now that you have a live bud, there are several ways to "force" it to

grow. For the limber stocks suggested herein, just bend the top of the

rootstock completely over and tie it to itself (Bending-Image 22). If

the stock is a little too large to bend readily, cut partway through it

at a point several inches above the bud and break it over at that cut

(Lopping-Image 23). For really large stocks, cut out a notch of bark on

the stock above the bud (Notching-Image 24). Notching does not force

buds as readily as bending or lopping.

|

|

Fig. 22

Bud forcing

by bending |

Fig. 23

Bud forcing

by lopping |

Within a week or so, the bud will begin to grow (Image 25), as will

previously dormant buds on the stock- note the just-broken rootstock

bud to the left of the new budling. Because you want to direct all of

the rootstock's energy into the new budling (Image 26), all other

sprouts should be broken off as soon as they appear. Be very careful

that you don't accidentally break off the budling, as it is very

brittle and easily snapped off at this stage. Disbudding will cease to

be necessary in a month or so, as the growth of the budling will

suppress other buds on the stock.

|

|

Fig. 24

Bud forcing

by notching |

Fig. 25 New bud starting to grow

|

|

|

Fig. 26

Disbud

rootstock sprout |

Fig. 27

Removal of

the top of the rootstock |

When the budling (the shoot that develops from

the scion bud in bud

grafting) reaches several inches in length and its stem hardens, it

should be loosely tied to the rootstock top. When it grows above the

bend (or break) of the rootstock, a bamboo, PVC pipe, wooden or other

type of stake should be inserted alongside the plant. The stake should

extend at least six inches into the soil and about two feet above the

soil. As the budling grows, continue to tie it loosely to the stake.

When the budling surpasses the top of the stake, cut off the rootstock

top at a slight downward angle opposite the base of the budling and as

close to it as possible (Image 27). Because the budling must be

"headed", cut it off just above the top of the stake (Image 28) to

force several buds at the top to grow to form the primary scaffold

limbs of the new tree.

The headed, finished tree (Image 29) is ready to plant. The entire

process from budding to finished tree requires about nine months, give

or take a couple of months depending on season, climate and care of the

growing budling.

|

|

Fig. 28

Budling

staked, tied and headed |

Fig. 29

Finished

tree ready to plant |

Publication from Aggie Horticulture®

The information, as it is presented on this Website, does not represent

an endorsement

by the State of Texas or any State agency.

Back to

Budding Techniques

Page

|

Publication from Aggie Horticulture®

|