Bitter

or Not Bitter? pdf

Kompong Notes

Coconut Grove, Florida,

Vol. 7. No. 1, March 15, 1972

By Dr. William T. Gillis

Antidesma

Provides Shade and Fruit pdf

The Miami News, Sunday Oct. 16, 1955

By Dr. Julia Morton

A New

antidesma from Indonesia

Fairchild Tropical Garden Bulletin 2(7):6-7. 1947

By Dr. David Fairchild

THERE IS so much interest

these days in the delicious

jelly made of

Antidesma bunius fruits that I think it

may be worth while to tell

of a new,

distinct variety, one that may

even be a distinct species,

that has fruited

here on The Kampong.

This is Number 259 of the Fairchild Garden Expedition. It has

grown from seed I collected on

March

16, 1940, in the market a little

village

in the island of

Madoera which lies just East of

Java.

I was

recovering from a

bad cut on

my leg, which I got by falling down

the

aft hatch of the yacht Cheng Hoduring

the fire

that broke out on her

as we were coasting along the shore

of northern Celebes. We had come to

Soerabaya to have

her ;repaired, and

before

I was able to get out much, a

friend of Captain Kilkenny, Miss

Vannin Manx, offered to motor me over

the

island of Madoera for

a glimpse of its fascinating

culture. We only

spent the day there but I wished it

could have

been much longer, for the soil

being strongly calcareous suggested that the

plants grown there

might do well in our

limestone soils here.

As I poked about in the markets

of the villages trying to

identify the

amazing variety of fruits and

vegetables which are always on show

in

them, my eye caught sight of

a bamboo

tray covered with Antidesma fruits.

Naturally,

I recognized them, but they struck

me as being somehow different from

those of my tree in the Kampong; the fruits were

smaller and

more

crowded on the stem.

I sent a little note with

the seeds

Marian cleaned and packed foe the Air

Post saying that I thought they

might be from another variety of this

interesting

tree, for when I compared the

fruits with the colored

illustrations of

Antidesma

Buriius

in Dr. J. J.

Ochse's book on

the "Fruit of Netherlands India"

I found they were distinctly different.

This was

in March of 1940. How little

I dreamed that a tree grown

from one of

those seeds would be the

first thing I would show on

our own

Kampong in Florida to my friend Ochse after

his arrival to be

Professor of Tropical Economic Botany in

the University of

Miami. How could I dream that while

it was growing into

a handsome tree and bearing quantities of

berries which the bluejays

took a great fancy

to, the whole picture of the Great East

would change

politically; that Japanese warriors would sweep over it, to be chased

off again in their turn; that Dr. Ochse and his family would spend

years in a prison camp and that Java would become a Republic! I cannot

now hold its thick dark leaves in my hand or hold up one of its bunches

of fruit in the sunlight without seeing the confused picture of the

events which followed that visit to Bankalang seven years ago.

This

new form of Antidesma has denser foliage, of a much thicker texture

than the ones we already knew. Its fruits are rounder and on longer

pedicels and the clusters are more compact. The whole little tree has a

distinctive character which I am unable to describe.

I have only

one seedling from the many seeds I sent in, and the fruits it produces

are larger than those I bought in the market. This fact reminds me that

my original tree from the Philippines and another received somewhat

later from the same place have fruits that differ slightly in form, and

one of them ripens much later than the other. I think that if anyone

would plant a thousand seeds of this Antidesma he might very likely get

some striking and much finer seedlings.

"Just why are you so interested in the Antidesma?" I am often asked.

And

my reply is that the tree is a shapely, handsome one, not too large for

any dooryard; its dark-green leaves are glossy and shine in the sun and

in summer it is very gay with its bunches of fruit, first green, then

white, then brilliant red and later a dull black. When the berries are

black they are not only good to eat right off the tree, but the

brilliant red juice makes the excellent jelly which, largely through

the efforts of Mrs. Helen E. Letchworth, has become popular under the

name of Antidesma Jelly! The story of the rise of the Antidesma Jelly

is told in Occasional Paper No. 6 of the Fairchild Tropical Garden.

And

now, with this other promising Antidesma growing here, we have another

step in our knowledge of this remarkable genus of fruit trees, out of

which may come who knows what new flavors. When some enterprising

person takes up their study we may get new jellies which will compete

with the best of the northern ones we became acquainted with in our

childhood — those of us Northerners who have emigrated into

south

Florida.

I recommend this Plant Immigrant from the island of

Madoera to the members of the Fairchild Garden Association who have a

place for a beautiful small tree in their yards. If they are fond of

Antidesma jelly they can gather the fruits, if not, they can leave them

for the bluejays and other birds to feast upon.

The Antidesmas as

Promising Fruit Trees for Florida

Florida Plant

Immigrants,

Occasional Paper No. 6., 1 Oct. 1, 1939.

Fairchild Tropical Garden

By David Fairchild

I

DO NOT KNOW of any better way to become acquainted with a new tree than

to grow it where you can see it every day. You cannot learn so very

much about it through reading and while you may get a faint idea of it

by seeing its photograph, still, the texture of its leaves, the odor of

its flowers, the taste of its fruit—which, after all are very

important

characters—cannot be conveyed to you except in a very general

way by

the printed word or by the halftone.

Even the botanist who has a herbarium specimen of it in his

collection, which he can pore over with his hand lens and compare with

other specimens of related species and learn a host of details which

can only be learned in that way, does not actually know it in the same

sense that the good observer does who grows it in his yard and cares

for it as a pet.

I realize that it is much easier to read about

a tree than to plant a seed and watch it grow into a tree and fight to

protect its life from fungus diseases and insect pests and even,

perhaps, against the indifference of one's gardener. It is regarding a

tree in my yard and some of its relatives that this brief paper is

written.

A short account of it without any illustrations

appeared in the Annual Report of the Florida State Horticultural

Society but I fear fell on deaf ears for I have heard nothing from it.

I trust this story may meet a kinder fate.

The first time I ever saw a plant of the genus

Antidesma,

to which the subject of my story belongs, was in the "arboretum" which

Mr. Charles Deering started and later for various reasons abandoned to

the real estate developers. Mr. Deering had received many new plants

from our Office of Plant Introduction in Washington and every time I

came to Florida I went to see how they were coming along. As I was

walking over the place I saw, half hidden by other plants, a small

bunch of brilliant red berries that reminded me faintly of a bunch of

currants.

Although sour, they were interesting and I remember

thinking that they would perhaps be exciting to a northern botanist who

has so few really new fruits to get excited over. The shrub was marked

Antidesma nitidum,

Tulasne. and it had grown from seed sent in from the Philippines. In

his description of it, Dr. C. F. Baker who sent it in and who was a

brother of Ray Stannard Baker, the author, and himself a great

entomologist, had this to say about it: "One of the finest local

shrubs, of good shape and covered with great numbers of pendant

clusters of small berries which are long, bright red, finally black,

and which are edible. This would make an important addition to

ornamental shrubs for warm countries."

Here was Baker's

recommended shrub and it was fruiting. Edward Simmonds and I thought

enough of it to take its portrait and record its behaviour and I have

its portrait before me now. But astonishing as it may seem to some of

my readers who imagine that introducing and establishing new plants is

easier than it is, this is practically all I have today to remind me

that

Antidesma nitidum

ever

flourished in America. This was in 1916, three years after Baker had

sent the seeds from Los Banos and we had given them the S. P. I. number

34695.

A few notes on its behaviour remain; one made just after

the great freeze of 1917 when the temperature in Mr. Deering's

arboretum went to 26° F. or lower, states that the group of

small trees

that had been in fruit had been killed back to the ground. I mourned

its disappearance from the garden. However, it had not been killed out,

for in 1922, on another visit I saw it again and recorded that "the

bushes of

Antidesma

nitidum

were literally loaded with dark red, almost black berries and I could

have picked half a gallon of these fruits, I feel sure. They taste a

little like blueberries but are a trifle resinous. They color the hands

like blueberries and would make stunning pies. This is a bush that we

should put in people's yards."

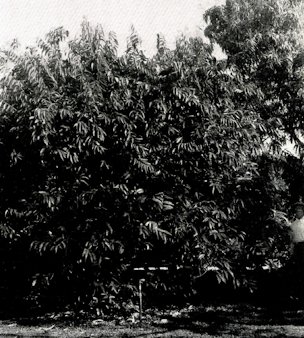

Tree of

Antidesma

bunius, on "The Kampong," that bears several bushels of

fruit every

August. It began bearing when six years old and might be compared with

a giant currant bush

for the clusters of fruit hang down in a similar way and make a

delicious jelly that is comparable

in color and quality to currant jelly. It has several names in Java and

the Philippines but

its scientific name has become established here. Nathan Sands, who

takes care of it, posing.

Whatever became of those bushy

little trees I have never known. The advent of the Florida boom swept

the "Deering Buena Vista Estate" into oblivion and, so far as I know,

the plant has disappeared from South Florida; unless some seedlings

have survived somewhere. Perhaps some reader of these lines can say.

But this was not the only antidesma on the Deering place and in 1917 I

noted that some plants of

Antidesma

bunius,

(L.) Spreng., one of its cousins, had been frozen to the ground. This

species had been also sent in from the Philippines the same year that

Baker had sent the other species. Since it came from an official of the

Bureau of Agriculture in Manila without any advertisement of any kind,

one of my colleagues in the Office in Washington hunted up the

literature about it and published under our Introduction number 43544 a

resume of the account of it given by the noted forester of British

India, Sir Dietrich Brandis, in his "Indian Trees," and what John

Lindley had to say about it in his "Treasury of Botany." This included

a statement that the leaves are used as a remedy for snake bites, the

bark for rope making, and that the wood when immersed in water becomes

black and as heavy as iron, etc. It was also stated that the very juicy

red fruits turn black when ripe and are about one-third of an inch in

diameter, sub acid in taste and used in Java for preserving, chiefly by

Europeans, and that they formerly sold for two pence a quart;

furthermore, that it was called the "Bignai."

It was not any of

these published accounts however, that led me to follow up my

acquaintance with this species. It was a remark made by Charles H.

Steffani, one of my former associates in the Brickell Avenue garden,

now the County Agent of Dade County. I enquired of him one day what had

become of the

Antidesma

nitidum

that had made such a promising beginning on Mr. Deering's place and he

replied, "I don't know, but it was not so good as the other species

anyway;

Antidesma bunius.

That's a wonderful tree. I have seen it loaded down with a bushel of

fruit and it makes a fine jelly." Whether it was he who secured me a

plant I do not recall. I have it in my notes that in 1928 the plant I

had set out north of my study was nine feet tall.

From that date

the struggle began. The beautiful, large, leathery, glossy leaves with

which its branches were covered and which gave the tree a very elegant

appearance, began to show signs of a scale insect. The undersides of

the leaves became coated with the translucent bodies of the insect from

the backs of which tiny drops of honeydew fell on the leaves below them

and in this a form of Sooty Mould fungus grew, forming dense,

soot-black felts that were most unsightly.

These disfigured the

foliage so that the young tree which I passed in going to my study,

became a disagreeable sight. "Volck" had fortunately been discovered so

my man Sands and I brought it into play. For a time though it was a

matter of doubt if it would be effective. Every few days I went over

the leaves to see if there were any live scales left with their caches

of young ones under their tortoise-shell-like bodies and, if I found

any the "Volck" had to be applied again. At last we were successful,

and slowly the beautiful foliage of the tree began to so charm me that

I did not care whether the tree fruited or not.

To my surprise

Sands announced one autumn that during my absence in August it had

borne a big crop of black fruits which the birds had taken because

nobody was there to pick and cook them. Since many of the fruits must

have fallen on the ground I looked for seedlings but there were none.

The next season Sands planted a lot of the seeds in a flat but none of

them grew and my suspicions were aroused and I dipped into the

literature; to discover that the

Antidesma

bunius is

a dioecious species, bearing only female flowers on one tree and males

on another. My tree was evidently a female, but there was no other tree

of the species anywhere about. How could it bear the full crops that it

had begun now to produce without any pollination? Again we tried to

raise seedlings, again without success. Thinking that there might be

somewhere in the Homestead region other trees of this species I

enquired of Dr. H. S. Wolfe and he informed me that there was a male

tree near the Subtropical Experiment Station and took me to see it when

it was in full bloom. Cutting a few male flower clusters I brought them

home and tied them carefully to female clusters on my tree which I

think ensured pollination, but again there was no germination of the

seeds that formed in the fruits borne by the clusters which had been

pollinated. I came to the conclusion that there was something wrong

perhaps in our seed-flat technique. I have since raised a few

seedlings, but only very few, from the many seeds we have planted.

Unlike most fruit trees, the Antidesma produces male flowers on one

tree and female flowers on

another. The date palm of the desert and the carob tree of Italian

hillsides does the same.

In this enlarged photograph the curious male flowers without petals or

sepals can be seen on

the flower spike on the right; each with its three stamens; each stamen

with two pollen masses

at its tip. The spike on the left has only female flowers, each with a

stigma seated on what will

become a berry when it matures. It will be well to have both male and

female trees on one's

place although my tree bore with no male anywhere near it.

In

the meantime I called the fruit of my antidesma to the attention of

Mrs. Helen E. Letchworth who had specialized in the making of jellies

and who was selling her product on the Miami Curb Market. She came with

her car the following August and together with her husband stripped the

tree of its load of fruit and made of them a very beautiful, dark red

jelly which she was able to sell to her customers at a good price. For

the past four years she has taken the fruits and made jelly from them

and we have had on our shelves jars of her antidesma jelly and tried it

on our many guests, getting from them universally favorable responses.

I have come to look upon this jelly as the equal of currant jelly, even

though there is involved here a matter of my childhood memories, for

currant jelly brings up the picture of my mother and the house where I

was born in Michigan and all sorts of delightful memories. But I can

imagine that as the years pass and antidesma jelly comes to be made in

South Florida as commonly as is currant jelly in Michigan, there may

come upon the stage a generation to whom childhood memories of it add

to its interest and make it preferred by them to currant jelly.

There

is another factor in the case of this antidesma. Whereas the currant

bushes growing in every garden in New England are known by some

varietal name such as the "Cherry," the "Currant," the "Fay," the

"Wilder" etc., and represent in each case a selected seedling from

which canes have been taken for propagation, my antidesma tree, which

by the merest chance, so to say, has come to stand in the "Kampong,"

may be an inferior seedling when compared -with other seedlings. Who

can tell what the best seedling of which the species is capable would

be like? Whether the berries may not be twice as large and juicier and

of better flavor than mine? Indeed I have just heard of a superior

strain of this species in the Philippines.

Pretending I am young

again and prepared to tackle the creation of a superlatively fine new

fruit of the antidesma species, I have imagined myself introducing the

best fruiters to be found among the over ninety species of the genus

Antidesma

which the botanical collectors have discovered scattered through the

jungles and prairies of the Old World tropics. As I pored over the

volumes of botanical descriptions, there opened before me a most

interesting vista of possibilities. It appears that the primitive

people of the tropical world have paid a good deal of attention to the

antidesma trees of their localities. My own tree thus became the

starting point for a journey of many thousands of miles on the other

side of the globe.

Before, however, opening up the book vista

concerning the antidesmas, there is a question which I would like to

raise. What would be an appropriate common name for this new class of

fruits? We have quite gaily called this

Antidesma bunius,

which happens to be the first species of which the fruit has been made

into jelly in South Florida, by its generic name of "antidesma."

Perhaps some have imagined that this use of the scientific name for its

common name gets us away from the tangle of common names. But what

shall we call the next species of antidesma (

A. nitidum

for example) to fruit and be used for jelly? It must have a common

name. If we call the first introduction "antidesma" will the situation

not be much as if when the first citrus fruit was introduced it took

the name "citrus" as its own common name. Let us imagine that this

first introduction was what we now call the lime. We could not very

well have called the lemon, when it was introduced, citrus too; and the

orange and the pomelo and the kumquat, for they are just as much citrus

species to the botanists as is the lime.

I fear we shall have to

recognize the chaotic character of common names and accept for the

antidesma some native East Indian name which was given to it, perhaps

centuries ago, in some native village by some unknown plantsman.

According to this principle,

Antidesma

bunius

might take the Philippine name of "Bignai" and any superior seedlings

of it that are worthy of special names be called the Smith Bignai or

the Jones Bignai which would bring them into line with the King Apple

and the Bartlett Pear. Perhaps some one will suggest we use the

complete scientific name and call our fruit jelly

Antidesma bunius

jelly and varieties of it the Smith

Antidesma bunius

jelly, etc. The popular demand for brevity will, I fear, never permit

of the use of such clumsy names, although I have to admit that the man

on the street does memorize "sulphanilamide" and the chemists have no

trouble with "hexamethylenediamine."

To return to the literature.

Antidesma

bunius is

known and given special names by the Battacks and Lampongs of Sumatra,

by the Buginese and natives of Celebes, and the people of Timor, that

far away island in the Timor Sea, north of Australia. It is referred to

as the "Bignai" or "Bignay" in the Philippines; in Java it is called

"Booni" by the Malays, "Wooni" by the Javanese and "Boorneh" by the

Madurese, while the Sundanese of West Java even distinguish by separate

names the male and the female trees.

It is a much cultivated

tree, according to J. J. Ochse who figures it in color in his beautiful

book "Fruits and Fruit Culture in the Dutch East Indies," which was

published in Java in 1931. The fruits when fresh are very much relished

by the natives, he says, and are used by them for syrups and jams and

also for putting into brandy. In that part of the world the

Antidesma bunius

bears its fruits at divers seasons but is most prolific in September

and October. The scientific name Antidesma was given the tree to denote

its use by the natives as a cure for snake bites, against which,

according to the Dutch botanist J. Burmann, who wrote the Flora of

Ceylon in 1737, it was used in those early days.

According to K.

Heyne, the Director of the museum in Buitenzorg, Java, where thousands

of tree products of the Malay Archipelago are exhibited, the bark of

our

Antidesma bunius

contains

an alkaloid and it has been used medicinally, as have also the leaves.

This does not indicate that the leaves are poisonous; on the contrary

they are edible, as is evidenced by the statement in Mr. J. J. Ochse's

other book, "The Vegetables of the Dutch East Indies," that "the young

leaves are eaten raw or steamed as a lablab." This Malay word stands

for a class of side dishes much used by the vegetarian inhabitants of

Java, consisting of leaves, fruits, sometimes also flowers or tubers,

usually eaten raw with rice but sometimes steamed, singed or cooked.

Since

my tree is just this moment coming into new leaf I have now as I write,

my mouth full of antidesma leaves. They are pleasantly acid, very

tender and altogether palatable. Who can say what vitamins they may

contain? In these days when the ideas of the chemists regarding the

synthetic enzymes which build up the protein molecules of our bodies

are in their infancy, who can predict where and in what plants new and

valuable enzymes will be found? My antidesma tree has acquired a new

interest since I learned that its leaves are a choice vegetable in Java.

It appears that this

Antidesma

bunius

was brought into the Moluccas before the time of Rumphius, for he

included it in his "Herbarium Ambionense," written before the days of

Linnaeus. It is therefore a very old cultivated tree indeed. It occurs

wild, according to Burkhill, from the foot of the Himalayas through

Ceylon and eastward as far as northern Australia. And for the reason

that it can struggle against the vicious "lalang" grass (

Imperata cylindrica)

which is slowly destroying millions of acres of virgin forest in the

oriental tropics every year, this tree is considered valuable even

aside from its edible fruits. It may find a place in the forestry

program in Florida.

But what does the literature say of the other species of this genus

Antidesma

of which there are ninety? According to Burkill's recently published

"Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsula"*

Antidesma alatum is

a small tree occurring from Siam southward and having scarlet fruits.

A cuspidatum is

common in the Malay peninsula and has fruits of which the birds are

fond.

A. gbaesembilla

is a shrub or small tree the acid leaves of which are edible as well as

the fruits.

A. montanum

is a small tree occurring from China to Borneo and Java and throughout

the Malay Peninsula and has fruits that the children eat.

A. stipulare

is a shrub found in the Moluccas and on the west coast of the Malay

Peninsula with edible fruits that are used as a medicine for children.

A. tomentosum is

found in all the mountainous parts of the Malay Peninsula and in Java

and its fruits are sometimes eaten.

A. velutinosum

is a 4 5-foot tree found from Burma through the western parts of

Malaysia and is very common in the Malay Peninsula and the fruits are

reported as edible.

One of the most delicious and beautiful of the jellies for sale on the

Miami market is made

from the almost black fruits of this

Antidesma bunius. When

in fruit the tree is completely

covered with these black clusters, making it a spectacular sight.

Ferdinand Pax, in his article on the Order

Euphorbiaceae—the order to which the antidesma

belongs—published in

Engler and Prantl's "Pflanzen Familien," an encyclopedic work on the

plants of the world, mentions West Africa, Sumatra, Japan, Madagascar,

the Liu Kiu Islands and the Fiji Islands as localities where species of

this genus are to be found. Curiously enough he says nothing about

whether the fruits are edible or not; doubtless many of them are. The

fact that this character is not mentioned in a botanical description

does not mean that the matter was overlooked by the author of the

description. It generally indicates that the collector of the specimens

which found their way into the herbarium or the museum where the books

were written, found the fruits difficult to preserve or he collected

the plant when it was not in fruit or was little interested in the

matter of the edible character of its fruits anyway and reported

nothing with regard to this feature.

According to Guilfoil in

his "Australian Plants Suitable for Gardens, Parks, Timber Preserves,

etc." Melbourne; a large fruited species

A. dallachyanum is

known in

Australia as the Herbert River Cherry, Queensland Cherry or Je-jo. This

appears to be one of the largest fruited species in the genus and the

juice is said to be found very grateful to persons suffering from

fever. The "Niggers-cord" is another species found in north Australia.

It is referred to

A.

ghaesembilla and is said to have edible fruits and be used

for medicine.

Enough

has probably been said to show that an unexplored field for any willing

plant breeder has been opened. One of the objects of this paper is to

illustrate the fact which long residence in South Florida has taught

me, that the plants I have about me are tied by close relationships to

others that might be even more interesting, had we only seeds of them

to grow and the time to watch them come into fruit. It goes without

saying that a search for these relatives of my

Antidesma bunius

tree would take one into some of the fascinatingly interesting places

of the world.

And

now, just as I am copying for publication this account of the tree in

my yard in Coconut Grove and preparing at the same time for a Fairchild

Garden Expedition to the islands of the Moluccas, there comes a letter

from Mrs. Harold Loomis who is stopping in "The Kampong" during our

absence in which she says: "The antidesmas are all gathered. When only

the big tree had been picked, the Letchworths compressed 52 gallons of

pure juice from the fruit. Isn't that amazing?"

I could hardly find a more enthusiastic note with which to close this

fragmentary account of the antidesmas.

Biological Nucleus Baddeck, Nova Scotia.

*

Burkill, I. H. A dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay

Peninsula. 2 vols. Publ. by the Crown Agents for the Colonies, 4

Millbank, London 1935. A most valuable book of reference.