From Advances in New Crops,

Proceedings of the First National Symposium NEW CROPS: Research,

Development, Economics

by D. N. Moriconi, M. C. Rush, and H. Flores

Tomatillo: A Potential

Vegetable Crop for Louisiana

1. INTRODUCTION

2. BOTANY

1. Plant Characteristics

2. Production

3. HORTICULTURE

4. TISSUE CULTURE

5. FUTURE PROSPECTS

6. REFERENCES

7. Fig. 1

8. Fig. 2

9. Fig. 3

10. Fig. 4

INTRODUCTION

Throughout

history humans have used some 3000 plant species for food. The recent

tendency has been to exploit fewer and fewer species and today, only

around 20 species supply most of the world's food. Many beneficial

plant species have been underused or have not been developed to their

full potential (Vietmeyer 1986). Useful plant species have often been

overlooked because they are native to the tropics, regions neglected by

the world's research institutions which are oriented toward crop

production in temperate zones.

There are several Solanaceous species with edible fruit that are

popular in Latin America in addition to tomato and chilies. Physalis ixocarpa

Brot.; commonly known as the husk tomato and by the Spanish names of

tomate de cascara, tomate verde, tomate de fresadilla, tomatillo, and

miltomate, is an important vegetable crop in the diets of Mexicans and

Central Americans. In Mexico, the fruits are used in the making of

chili sauce and dressings for popular dishes such as tacos and

enchiladas. P. ixocarpa

is

gaining ground as a new crop in California due to the increased

popularity of Mexican food in the United States (Quiros 1984) and has

production potential in the southern United States. In Louisiana,

tomatillo imported from Mexico is sold as a fresh fruit in a few

grocery stores. There is a potential market for fresh produce and the

Louisiana sauce industry may be interested in opening a new ethnic

market for their products. Developing a new crop is a difficult and

complex process. One way is to import an exotic crop from areas where

the crop is already grown or consumed and adapt it to local conditions

(Laidig et al. 1983). It appears that P. ixocarpa

has potential as a commercial crop in Louisiana. Our interest in

tomatillo is to satisfy the regional demand for fresh product and to

develop a new processed product for the Louisiana canning and sauce

industry.

A variety of world-wide, national and local economic

factors have combined to cause a reduction in the income of Louisiana

farmers. Along with other areas of the country, Louisiana has begun to

search for crops that would diversify its agriculture (Hamm 1985). The

estimated net return per unit area of land is high in vegetables when

the volume of production and sales is sufficient to amortize the

required investment Hinson and Cannon (1988) consider that 350,000 to

400,000 ha are suitable for vegetable production in Louisiana. The

light-textured alluvial soils along the Mississippi, Red, and Ouachita

rivers are highly appropriate for vegetable crops. Climate and soil

type are major factors that must be considered for vegetable

production. Generally, the rainfall in Louisiana is sufficient for crop

production without irrigation; however, the pattern of rain is such

that some crops could be destroyed by excessive rainfall unless

drainage is provided. In other areas, irrigation after transplanting

would be necessary for survival of transplants. The area planted to

vegetable crops has increased from 4,300 ha in 1980 to 7,300 ha in

1986. Louisiana clearly has the resources for producing vegetable

crops. Both land and water are abundant, although water must be

managed. A local supply of labor is available, due to the high

unemployment rate (Hinson and Cannon 1988).

Louisiana has a

total of 15 commercial fruit and vegetable processing plants. Six of

the plants are exclusively canning factories. Eight plants produce

pickled products, hot pepper sauce, and other table sauces for

seasoning. The remaining processing plants produce products in bulk for

further processing. Except for two plants, the processing plants in

Louisiana are located in the south central section. Sauce plants are in

Saint Martin parish (Acadian Pepper Co., Bruces Food Co., Cajun Chef

Products Inc., and Landry Brothers), Iberia parish (Durke-French Foods

Inc., McIlhenny Company East, and B.F. Trappey's Sons, Inc.), East

Carroll parish (Panola Pepper Co.), and Orleans parish (Baumer Foods

Inc.) (Broussard and Hinson 1988).

The total volume of table

sauces, pickled, and other items processed in Louisiana is around

22,277,000 kg with an estimated value of $58,427,000. Table sauces

accounted for approximately 77% of the total volume (Broussard and

Hinson 1988). The increase in table sauce production may be a result of

the popularity of cajun food observed across the U.S. Studies have been

conducted toward developing tomatoes for processing in Louisiana, but

the high summer temperatures cause flower abscision and reduce crop

yield. Tomatillo plants are known to grow and set fruit at high

temperatures. The Yucatan peninsula, the main area for tomatillo

production in Mexico, has daily mean temperatures similar to those in

Louisiana during the summers and maximum temperatures are higher in the

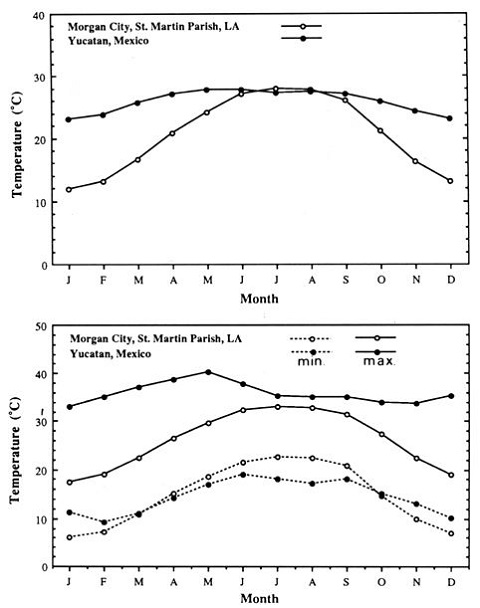

Yucatan throughout the year than in Louisiana (Fig.

1).

The increase in the popularity of Mexican food in the last decade, and

the amount of Mexican sauce available in the grocery stores indicates a

high potential for tomatillo as an ingredient of canned taco and

enchilada sauces. Tomatillo, a main component in traditionally made

taco and enchilada sauces in Mexico and Central America could be

produced in Louisiana and sold in the fresh vegetable markets of the

Southern U.S. or processed by Louisiana companies in sauces.

BOTANY

The genus Physalis,

established by Linneaus in 1753, contains about 100 species of annual

and perennial herbs (Willis 1966). The genus is characterized by the

presence of pendant flowers and an inflated fruiting calyx which

encloses the berry (Sullivan 1984). Four species are cultivated in

different parts of the world for their fruit: P. peruviana L.

(cape gooseberry, uchuba) and P.

pruinosa L. (ground cherry, husk tomato) are used as jam

fruits; P. alkekengi

L. (Chinese lantern) is used as an ornamental; and P. ixocarpa Brot.

(tomatillo, tomate de cascara) is used as a vegetable or for sauces.

Several species of Physalis

are widespread in America as endemic weed species. Six important Physalis

spp. are prevalent in the phytogeographic region of Mesoamerica

(Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and

Panama, and the Mexican states of Chiapas, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo): P. angulata L., P. cordata Mill., P. gracilis Miers, P. ignota Britt., P. lagascae R.

& S., and P.

pubescens L. (Gentry and D'Arcy 1986). These Physalis

spp. can be intercrossed, but incompatibility has been found (Pandey

1957, Quiros 1984). The basic chromosome number of the genus is N=12

and most species are diploid; P.

peruviana is a tetraploid (Menzel 1951).

Tomatillo has been known to botanists for nearly 400 years as P. philadelphica

Lam. Francisco Hernandez in 1651 described two varieties from numerous

plant types called tomate by the Aztecs. Botanists have suggested that

the small-fruited miltomate is a wild-type plant, whereas, the

tomatillo is a domesticated plant that derives from plants similar, if

not identical, to miltomate (Hudson 1986). The specific boundaries in Physalis

are poorly defined with some duplication of names and many changes in

the nomenclature during the last 50 years. The complexity of the genus

is caused mainly by the wide range of genetic variability present

presumably resulting from interspecific hybridization (Menzel 1951,

1957; Waterfall 1958) and also by the ambiguity of the earlier

taxonomic descriptions (Raja-Rao 1979). For example, P. aequata Jacq.

and P. capscicifolia

Rydb are considered synonymous with P. ixocarpa.

To clarify the taxonomic classification of Physalis, Menzel

(1951, 1957) and Waterfall (1967) made extensive cytologic and

taxonomic studies of the genus. Menzel reduced P. philadelphica to

synonymy under the variable P.

ixocarpa

Brot. a name that had to come to be widely used for the domesticated

tomatillo (Hudson 1986). The only apparent difference between the two

species was the length of the peduncle, with the peduncle of P. ixocarpa shorter

than that of P.

philadelphica.

Waterfall (1958) accepted this nomenclature when studying the species

of North Mexico, but he reversed himself when he analyzed Physalis spp. from

Mexico and Central America (Waterfall 1967). He incorporated the

small-flowered P.

ixocarpa within the broader limits of P. philadelphica.

Fernandes (1974) made a thorough investigation of this nomenclatural

problem and concluded that P.

ixocarpa is a distinct species, different from P. philadelphica

based on previous cytological evidence, the distinctive sigma, and the

small flowers of the type. Chromosome morphology has recently been used

to understand the interspecific relationships in the genus. Gottschalk

(1954), Raja-Rao (1979), Venkateswarlu and Raja-Rao (1977, 1979a, b),

and Raja-Rao and Lydia-Prasad (1984) studied the morphology of

chromosomes during the pachytene stage with most important Physalis

spp. and demonstrated cytological differences between the species.

Nevertheless, the taxonomic complexity of the genus is not yet

clarified, especially between P.

ixocarpa and P.

philadelphica.

HORTICULTURE

Plant

Characteristics

Plants in the genus Physalis

have herbaceous stems. Some have short to elongated rhizomes, the

leaves are usually broadly ovate to linear and generally alternate. The

flowers are solitary in the axis of the leaves, sometime pendant in the

axillary branches causing them to appear to be axillary between the two

branches. The pendant blossoms are often hidden by the foliage and many

of the flowers hang just above the ground (Sullivan 1986). The flowers

have corollas campanulate to rotate with the petal borders reflexed.

Petals are usually yellow with a dark purple spot near the base of each

petal. The calyx is united, with lobes more than one half its length.

The androecium has five stamens with the filaments attached to the base

of the corolla tube. The anthers are ovate-oblong and dehiscent by

lateral slits. The fruit is a two carpet, many seeded-berry (Waterfall

1958). There are several reports concerned with the development and

growth of tomatillo plants (Mulato-Brito et al. 1985; Cartujano-Escobar

et al. 1985a, b), and we have 2 years of experience with tomatillo

growing in Louisiana.

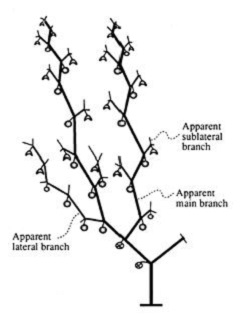

Tomatillo seedlings form a single shoot

which has three to five internodes above the cotyledons. The last

internode ends with a flower, one leaf and two lateral ramifications.

Each ramification has one node which terminates in the same pattern,

one end flower, one leaf and two branches. This pattern continues until

senescence, "with the exception that when two leaves are formed there

is no further branching (Fig. 2).

One

characteristic of the main branches is that the internodes differ in

length and have many adventitious roots. When these roots contact soil,

they grow into the soil and are independent of the main root system.

The

number of fruits set is variable, but generally fruit are set until the

10th and 11th weeks after emergence. Tomatillo is similar to tomato

plants, in that the biggest fruit are from the first flowers on the

main branches. The lateral and sublateral branches produce more flower

buds but they abscise and do not produce harvestable fruit.

Mulato-Brito et al. (1985) reported that the greater total number of

nodes on the lateral and sublateral branches produce more fruits than

the main branches, but that those fruits rarely reach commercial size.

Maximum fruit production is reached by 11 weeks after emergence. The

high number of fruits present at this time compete with each other for

the available nutrient supply. Most of the fruit on lateral branches

are

dropped or they do not reach commercial size (Cartujano-Escobar et al.

1985b).

A breeding program should select for a determinant plant

type suitable for mechanical harvesting of tomatillo. The elimination

of sublateral branch production and reduction of internode number in

lateral branches would be very important for restricting fruit

production to a short period of time.

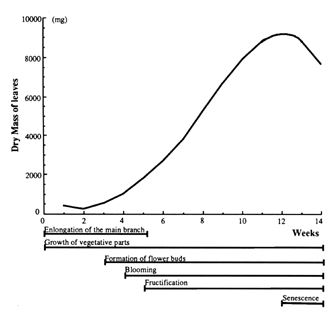

The seed germinates in

7-10 days, followed by elongation of the primary shoot for 4 weeks. The

first flower bud is formed before the elongation of the primary shoot

end, which is around the 3rd or 4th week after emergence, and flowering

continues until senescence of the plant. The first flower appears 4 to

5 weeks after emergence and the first fruit appears one week later,

reaching 3 cm in diameter at 8 weeks. The symptoms of senescence are

visible after 12 weeks, with the plant reaching total senescence at 14

or 15 weeks after emergence (Fig. 3).

The

growing period for tomatillo is short (3 to 4 months) and several

overlapping crops could be produced in Louisiana. The only limit to

plant growth is low temperatures. The growth of tomatillo is poor at

temperatures of 16-18°.C or less. Plants grown in Louisiana

during the

hottest part of the summer produced marketable size fruits (up to 7 cm

in diameter).

Production

Tomatillo

is an important vegetable in Mexico and Central America, where it is

claimed that there is no acceptable substitute for this fruit in making

green sauce (moles) which is served together with regional dishes

(Saray-Meza et al. 1978). Its consumption in central Mexico is about

10% of the total consumption of tomato (Cartujano-Escobar et al.

1985a). In Mexico and Guatemala it is common to find escaped tomatillo

as a weed. Tomatillo originated in Mexico and probably was domesticated

in pre-Columbian times. The plant is an annual, 1-1.5 m in height,

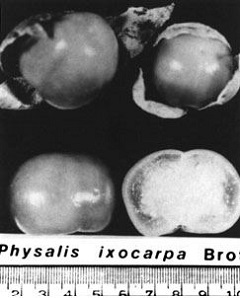

acclimatized to tropical-subtropical humid conditions. These plants

have numerous branches in a dichotomous pattern. The fruit is enclosed

in a husk (enlarged purple veined calyx), but unlike the cape

gooseberry, the inflated calyx stops growing before the berry and is

usually split by the expanding berry (Fig.

4).

The berry is large, round, sticky, green or purplish, high in ascorbic

acid (36 mg/100 g), nicotinic acid (3.5 mg/100 g) and in solids (9%) as

compared to the tomato (6%) (Yamaguchi 1983). The pulp is glutinous, a

little sweeter than tomato, and the flavor is somewhat similar to apple

according to Herklots (1972). The fruit is normally cooked before it is

consumed.

Mexico.

Tomatillo is cultivated in Mexico from the second week of May to the

middle of December, which would correspond to temperatures from mid-May

to mid-October in Louisiana. It is cultivated with and without

irrigation. Tomatillo in central Mexico follows the culture of

sugarcane (Saccharum

officinarum L.) or rice (Oryza sativa

L.). These are also major crops in Louisiana. Thus, the crop rotation

and climatic conditions would be similar in Louisiana. Tomatillo

requires a well prepared soil, generally with furrows 25-cm deep, and

intensive tillage to allow good development of the root system

(Grazon-Tizanado and Garay-Alvarez 1978).

The number of harvests

in Mexico varies with the plant type and quality of the product. Four

to six harvests is normal. Fruit removal should begin when three or

four fruit are mature on each plant which is around 55 to 70 days after

transplanting. A fruit is considered mature when the berry fills the

husk and in some cases breaks it. The size of husk and fruit, the

color, and the flavor of the fruit is variable. The fruit can be green

to yellowish-green or even purple and the flavor can range from sweet

to acid sweet (Villanueva and Loya-Ramirez 1976). The criollas types of

tomatillo yield about 15,000 kg/ha in Mexico. The cultivar `Rendidora'

yields about 25,000 kg/ha. `Rendidora' had about 35% of the total

production in Mexico with large (5 to 7 cm) size fruit and 85% of the

fruit were of commercial quality (Saray-Meza et al. 1978).

Tomatillo

is self-incompatible, so all plants are hybrids. Pollination is by

insects. Cross pollination with other cultivars or other Physalis

spp. would be possible if the plants are closer than 500 m. All seed

production must be carried out in isolation. Saray-Meza et al. (1978)

reported that 10 kg of fruit yields 100 to 200 g of seeds. Plant

viruses can reduce tomatillo yields by 30 to 40%. Delgado-Sanchez

(1986) described a complex of at least three different viruses

affecting tomatillo.

Louisiana.

Plants of P. ixocarpa

were grown in the greenhouse in 1986 with seeds from a single fruit.

Seeds were germinated in petri plates with wet filter paper. The

plantlets were transferred to 7.5 cm pots and placed in the greenhouse.

When plants reached 4 or 5 leaves (4 weeks), they were transplanted to

the field. The field was ploughed twice at 25-30 cm deep, fertilized

with 50 kg/ha 15-15-15 (NPK) and covered with black plastic mulch

before transplanting. Rows were 120 cm apart with 60 cm between plants.

Tomatillo plants were transplanted to the field on June 6, June 25,

July 15, and August 1. Insecticide was applied at 15 day intervals. The

first harvest was made after 6 weeks and harvesting continued at 10 day

intervals for a total of seven harvests during the plant cycle. The

estimated yield was 13,450 kg/ha. There was variation between plants in

size, leaf shape, fruit size and shape, and yield. Fruit damage by

lepidopterous insects was severe, probably reducing the yield by 20 to

30%. No major diseases were observed.

TISSUE CULTURE

A

tissue culture system to exploit somaclonal variation in tomatillo was

developed in our laboratory (Moriconi et al. 1988). Leaf disc or

hypocotyle and epicotyle explants were plated onto Murashige-Skoog

medium (MS) (Murashige and Skoog 1962) containing 3% sucrose, 0.25%

Gelrite or 0.8% agar, B5 vitamins (Gamborg et al. 1968) and 4 mg/liter

2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D). Callus forming on the explant

pieces was transferred to basal MS medium supplemented with 1.0

mg/liter benzylamino-purine (BA) and 0.5 mg/liter indole-3-acetic acid

(IAA). Shoots from organogenesis or embryogenesis formed on the callus

after 6 to 8 weeks of incubation at 26°C, under cool white

fluorescent

lamps, using a 16 hour photoperiod. These shoots developed into normal

plants and could be transferred to a peat-soil mix in the greenhouse.

For

micropropagation, single nodes from sterile regenerated plants were

subcultured in Magenta GA7 vessels containing a medium consisting of

basal MS, B5 vitamins, 0.25% Gelrite, and 10 g/liter sucrose. These

plated nodes readily proliferated shoots from buds. Surface sterilized

stem pieces from seed-grown plants also produced numerous shoots from

buds when plated on this medium. Micropropagation will be useful in

maintaining lines for hybridization for seed production and for

producing large numbers of cloned plants from high yielding,

horticulturally superior plants.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

The

prospects for utilizing tomatillo in the sauce industry are excellent

Sauce made from tomatillo by the Herdex company in Mexico, is being

distributed in the United States by Festin Food Corporation of

Carlsbad, California. Tomatillo is also the main constituent of the

taco sauce packed and distributed by La Victoria Foods, Inc. of City of

Industry, California. Presently Mexico is the source of tomatillos used

commercially in the United States. Local sources of tomatillo should

find an industrial market if a consistent supply can be provided

economically.

Tomatillo is genetically highly variable. To

become a viable commercial crop it will be necessary to develop plants

with uniform fruit size suitable for mechanical harvesting. Mechanical

harvesting requires a determinate plant with most of the fruit maturing

at about the same time. The husk should be loose at maturity and the

fruit should detach easily from the pedicel. Breeding programs should

give these characteristics priority

REFERENCES

Broussard, K.A., and R.A. Hinson. 1988. Commercial fruit and vegetable

processing operations in Louisiana, 1986-1987 season. Louisiana Agr.

Exp. Sta. A.E.A. Info Ser. 68. Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

Cartujano-Escobar, F., L. Jankiewicz, V.M. Fernandez-Orduna, and J.

Mulato-Brito. 1985a. The development of the husk tomato plant (Physalis ixocarpa

Brot) I. Aerial vegetative parts. Acta Soc. Bot Pol. 54:327-338.

Cartujano-Escobar, F., L. Jankiewicz, V.M. Fernandez-Orduna, and J.

Mulato-Brito. 1985b. The development of the husk tomato plant (Physalis ixocarpa

Brot) 11. Reproductive parts. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 54:339-349.

Fernandes, R.B. 1974. Sur

I'identification d'une espece de Physalis

souspontanee au Portugal. Bol Soc. Brot. 44:343-366.

Gamborg, O.L., R A. Miller, and K. Ojima. 1968. Nutrient requirements

of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Exp. Cell Res. 50:151-158.

Gentry, J.J., and W.G. D'Arcy. 1986. Solanaceae of Mesoamerica. p.

2-26. In: W.G. D'Arcy (ed.). Solanaceae, biology and systematics.

Columbia Univ. Press, New York.

Gottschalk, W.

1954. Die chromosomenstruktur der solanaceae unter berucksichtigung

phylogenetischer fragestellungen. Chromosoma 6:539-626.

Grazon-Tiznado, J.A., and R. Garay-Alvarez. 1978. El cultivo del tomate

de cascara en el estado de Hidalgo. Circular CIAMEC N 58. Mexico.

Hamm, S.R. 1985. Profile: consumption and production of the U.S.

vegetable industry p. 4-13. In: E. Estes (ed.). Proc. of analyzing the

potential for alternative fruit and vegetable crop production seminar.

North Carolina Agr. Res. Serv- and Tennessee Valley Authority

Herklots, G.A. C. 1972. Vegetables in

South-East Asia. Hafner Press. New York p. 372-376.

Hinson, R.A., and J.M. Cannon. 1988. Vegetable crop potential in

Louisiana. Louisiana State Univ. Agr. Ctr., Louisiana State University,

Baton Rouge.

Hudson, W.D. 1986. Relationships of

domesticated and wild Physalis

philadelphica. p. 416-432. In: W. G. D'Arcy (ed.).

Solanaceae, Biology and Systematics. Columbia Univ. Press, New York.

Laidig, G.L., E.G. Knox, and R.A. Buchanan. 1983. Underexploited crops.

p. 38-64. In: W.R. Sharp, D.A. Evans, P.V. Ammirato and Y. Yamada

(eds.). Handbook of plant cell culture, crop species. Macmillan, New

York.

Menzel, M.Y. 1951. The cytotaxonomy and

genetics of Physalis.

Proc. Amer. Phil. Soc 95:132-183.

Menzel, M.Y. 1957. Cytotaxonomic studies

of Florida coastal species of Physalis.

Yrbk Amer. Phil. Soc. 1957:262-266.

Moriconi, D.N., H. Flores, and M.C.

Rush. 1988. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in Physalis ixocarpa.

Brot. Plant Physiol. Suppl. 86:118. (Abstr.)

Mosino-Aleman, P.A., and E. Garcia. 1974. The climate of Mexico. p.

345-404. In: R.A. Bryson and F. K. Hare (eds.) World survey of

climatology Vol. 11. Climates of North America. Elsevier Scientific

Publ. Co. New York.

Mulato-Brito, J., L.

Jankiewicz, V.M. Fernandez-Orduna, F. Cartujano-Escobar, and L.M.

Serrano-Covarrubias. 1985. Growth, fructification and plastochron index

of different branches in the crown of the husk tomato (Physalis ixocarpa

Brot.). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 54:195-206.

Murashige, T., and F. Skoog. 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth

and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15:473-497.

National Climatic Data Center. 1985. Climatography of the United States

No 20. Climate summaries for selected sites, 1951-80. Louisiana.

Depart. of Commerce, Asheville, NC.

Pandey, K.K. 1957. Genetics of

self-incompatibility in Physalis

ixocarpa Brot.: a new system. Amer. J. Bot. 44:879-887.

Quiros, C.F. 1984. Overview of the

genetics and breeding of husk tomato. HortScience 19:872-874.

Raja-Rao, K.G. 1979. Morphology of the

pachytene chromosomes of tomatillo (Physalis

ixocarpa Brot.). Indian Bot. 2:209-213.

Raja-Rao, K.G., and Y. Lydia-Prasad.

1984. Pachytene chromosomes of Physalis

lanceifolia Ness. Cytologia 49:567-572.

Rick, C.M. 1987. Genetic resources in Lycopersicon. p. 17-26. In: D.J.

Nevins, and R.A. Jones (eds.). Tomato biotechnology. Alan R. Liss, New

York.

Saray-Meza, C.R., A Palacios A., and E.

Villanueva. 1978. Rendidora, nueva varieded de tomate de cascara. El

Campo 54:17-21.

Sullivan, J.R. 1984. Pollination biology

of Physalis viscosa

var. cinerascens (solanaceae). Amer. J. Bot. 71:815-820.

Sullivan, J.R. 1986. Reproductive

biology of Physalis

viscosa. p. 274-283. In: W.G. D'Arcy (ed.). Solanaceae,

biology and systematics. Columbia Univ. Press, New York.

Venkateswarlu, J., and K.G. Raja-Rao.

1977. Morphology of the pachytene chromosomes of Physalis philadelphica

Lam. Caryologia 30:435440.

Venkateswarlu, J., and K.G. Raja-Rao.

1979a. Morphology of the pachytene chromosomes of Physalis pubescens

L. Cytologia 44:161-166.

Venkateswarlu, J., and K. G. Raja-Rao.

1979b. Morphology of the pachytene chromosomes of Physalis angulate

L. Cytologia 44:557-560.

Vietmeyer, N.D. 1986. Lesser-know plants

of potential use in agriculture and forestry Science 232:1379-1384.

Villanueva, E., and J. Loya-Ramirez. 1976. El cultivo de tomate de

cascara en el estado de Morelos. Circular CIAMEC N 57 Zacatepec,

Morelo, Mexico. p. 11.

Waterfall, U.T. 1958. A taxonomic study

of the genus Physalis

in North America north of Mexico. Rhodora 60:107-114.

Waterfall, U.T. 1967. Physalis in Mexico,

Central America, and the West Indies. Rhodora 69:82-120.

Willis, J.C. 1966. A dictionary of the

flowering plants and ferns. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK.

Yamaguchi, M. 1983. World vegetables,

principles, production and nutritive values. AVI., Westport, CT.

Fig. 1. Daily

mean temperatures (top), and maximum and minimum temperatures (bottom)

of Yucatan, Mexico (period 1931-1960) and Morgan City, Louisiana

(period 1951-1980). Sources: National Climatic Data Center (1985), and

Mosino and Garcia (1974).

Fig. 2. Diagram

of the tomatillo plant in full development showing fruit setting over

different branches. Modified from Cartujano-Escobar et al. (1985a).

Fig. 3. Growth

curve and phenological stages of tomatillo in Morelos Mexico. Modified

from Mulato-Brito et al. (1985) and Cartujano-Escobar et al. (1985a).

Fig. 4. Tomatillo

fruit at maturity. The fruit break open the enveloping husk. The fruit

are greenish-yellow, with a slightly sticky surface, high in solids and

containing many seeds.

Last update September 4, 1997 by aw

|

|